|

April 13-15, 2007

Salida, Colorado

Anderson Ranch Fire — August, 1997

Investigation Report

Action Plan

Communicating Intent and Imparting Presence

Taskbook Opportunities

Salida Chamber of Commerce Visitor

Information

|

Communicating Intent

and

Imparting Presence

Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence G Shattuck, U.S. Army

An Empirical Study of

Commander’s Intent

Command and control processes are not unique to the Army, or even to

the military. Many other organizations have practices to develop plans

and procedures and then implement them at some other time and place

as the senior member of the organization desires.despite complexity

or uncertainty. But no other organization works as hard at explicitly

formulating and communicating intent to its subordinates as the US

Army. The concept of intent is written into our doctrine and taught

in our schools. Yet, as a profession, we have some work to do before

we effectively formulate, communicate, interpret and implement intent.

In an empirical study, four active duty battalions (two armor, one mechanized

infantry and one ground cavalry squadron) participated in the research.

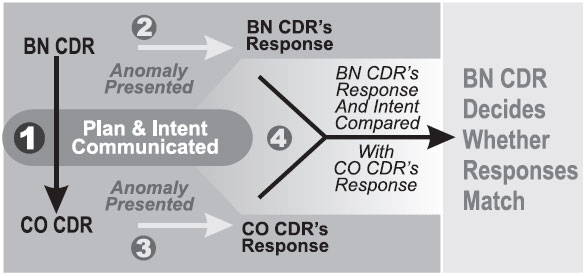

Figure 1 describes the simulation that was used to collect data. The

battalion commanders and their operations officers knew the research

was investigating the intent process within their organizations, but

the company commanders were only told that the process was a garrison-based

exercise to provide the battalion with practice in developing operation

orders.

Figure 1. Data Collection

from battalion and company commanders.

The battalion commanders were issued a brigade operation order (OPORD)

with maps and overlays that tasked the battalion to defend in sector

and to be prepared to counterattack. The OPORD was based on an actual

NTC scenario. The battalion commanders and their staffs had one week

to develop a battalion OPORD with all appendixes and overlays. They then

disseminated the orders, which included statements of intent, to subordinate

company commanders. These company commanders (four per battalion) were

given a week to develop their own OPORDs and then briefed them back to

the battalion commanders.

An investigator reviewed copies of the battalion and company OPORDs.

Then, two situation reports (SITREPs) were created for each battalion.

In the first SITREP, the companies were blocked from completing their

specific mission but could still achieve the higher-order objectives

of the battalion commander. In the second SITREP, the companies had completed

their missions with relative ease and had to decide what to do next.

In both cases, the intent statement of the battalion commanders provided

sufficient information to help the company commanders respond to the

SITREPs.

The battalion commanders were presented with the SITREPs and asked how

they expected the subordinate company commanders to respond to each SITREP.

Their answers became the basis for evaluating the responses of their

subordinate company commanders. The SITREPs were then presented to the

company commanders. The responses of the company commanders were recorded.

The battalion commanders were shown the responses of their subordinates

and asked to judge those responses relative to their own.

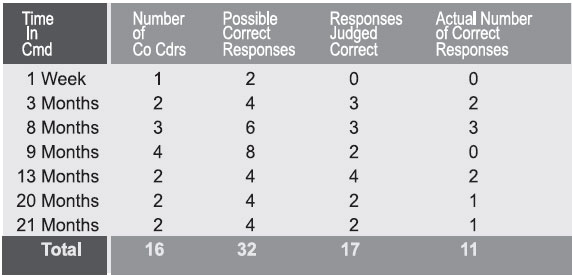

Four battalions, each with four company commanders that were given two

SITREPs, generated 32 episodes. The battalion commanders judged that

the company commander’s responses matched their intent in only

17 of the 32 episodes (53 percent). In three episodes, however, the responses

matched only by coincidence—the company commanders made their decision

based not on their understanding of the battalion commander’s intent

but because they misinterpreted the information available to them. In

three other episodes, although the battalion commanders judged the decision

of the company commanders to match their own, they were, in fact, substantially

different. Battalion commanders considered them a match because the company

commanders were “thinking along the right lines.” If these

six episodes are considered mismatches, then the responses matched in

only 11of 32 episodes, or 34 percent.

Successful company

commanders that matched their battalion commander’s

intent initially determined the disposition of friendly and enemy forces.

They specifically referenced procedures and the intent statement in the

battalion OPORD. They also acknowledged that they had to coordinate their

activities with commanders of adjacent units prior to taking any action.

The amount of time the company commanders had worked for their battalion

commanders varied from as little as one week to as long as 21 months. Figure 2 summarizes

the responses of the company commanders to the SITREPs based on the length

of time they had worked for their battalion commanders.

The data do not suggest that the ability of the company commanders to

match their battalion commander’s intent was linked to the length

of time the company commanders had been in command. However, the research

did reveal several interesting patterns in the performance of subordinate

commanders.

Figure 2. Summary of

company commander responses based on their time in command.

Discussion of empirical findings. Successful company commanders that

matched their battalion commander’s intent initially determined

the disposition of friendly and enemy forces. They specifically referenced

procedures and the intent statement in the battalion OPORD. They also

acknowledged that they

had to coordinate their activities with commanders of adjacent units

prior to taking any action.

There are

four equally important components: formulation, communication, interpretation

and implementation. The first two components—formulation

and communication—are the senior commander’s responsibility.

. . . Our officer education system emphasizes formulation and students

have virtually no opportunity to practice the other three components.

Unsuccessful company commanders generally did not refer to the battalion

commander’s statement of intent. In addition, unsuccessful commanders

exhibited several other behaviors. Some commanders exhibited flawed tactical

knowledge. For example, one commander’s response to a SITREP was

to reposition his unit on the battlefield. In the scenario, however,

there was insufficient time to accomplish this maneuver. The enemy would

have attacked the company on its flank as it moved. A few commanders

had a low tolerance for situational uncertainty. They decided not to

act without more information to reduce their uncertainty. In some instances,

commanders misassessed available information. Even though they were given

information on the status of enemy units, for example, they did not incorporate

it into their mental model of the battlefield. Some commanders also exhibited

a rigid adherence to procedures despite new information that indicated

they were facing a novel, unanticipated situation. When a major, unanticipated

event occurred on an adjacent part of the battlefield, these commanders

would not deviate from their assigned mission, even though the event

jeopardized the higher-order goals of the system. Finally, the study

indicated that, in some instances, battalion and company commanders disagreed

concerning doctrinal terms. If a battalion commander and a company commander

do not have the same definition of “delay,” the subordinate

commander may make an erroneous decision.

The feedback from all four battalion commanders participating in the

study indicated that it was worthwhile and they leaned a great deal.

The results gave them a clear picture of how successfully they communicated

intent to their subordinate commanders. In addition, the results identified

areas that each unit needed to improve in formulating, communicating,

interpreting and implementing intent.

Responsibilities of senior and subordinate commanders. There are four

equally important components: formulation, communication, interpretation

and implementation. The first two components—formulation and communication—are

the senior commander’s responsibility. Subordinate commanders interpret

and implement intent. Subordinate commanders at a given echelon will

also be senior commanders and must formulate and communicate their intent

to the next lower echelon. Our officer education system emphasizes formulation.

Students at combat arms advanced courses, CAS3 , Command and General

Staff College (CGSC) and even Army War College students, practice writing

intent statements based on information provided by their instructors

(including higher commander’s intent, mission statement, information

concerning friendly and enemy forces and task organization). The final

product in these schools is usually an OPORD that is briefed to an instructor.

However, students have virtually no opportunity to practice the other

three components.

Training officers in the classroom to communicate, interpret and implement

intent is extremely difficult because these components are context-based—personality-

and situation-dependent. Interpreting and implementing intent is especially

problematic. Senior commanders formulate intent prior to hostilities,

based on their vision of the battlefield. They also communicate their

intent to subordinate commanders, who interpret it prior to hostilities.

If the battle goes according to the vision, there is no need for subordinate

commanders to refer to the intent statement. It is only when the battle

deviates from the plan that the intent statement becomes significant.

However, the context in which the intent was developed (the senior commanders’ vision)

has now changed. Subordinate commanders now must interpret and implement

the intent based on a new, probably unanticipated context. As stated

earlier, our military schools do not teach subordinate commanders to

interpret and implement intent. The results of the research reported

earlier indicate that subordinate commanders may not be learning these

skills in the field either.

<<< continue

reading—Communicating Intent and Imparting Presence, Unit Intent

Training >>>

|