South

Canyon Fire South

Canyon Fire

1994

6 Minutes for Safety — 2009

Fire Behavior Report, 1998

Fire Environment

- July 2 to

Evening of July 5

- July

5, 2230 to July 6, 1530

- July 6, 1530

to 1600

- July 6, 1600

to 1603

- July

6, 1603 to 1609

- July 6, 1609

to 1610

- July 6, 1610

to 1611

- July 6, 1611

to 1614

- July 6, 1614

to 1623

- July

6, 1622 to 1830

- July

6, 1830 to July 11

References

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

|

Fire

Behavior Associated with the 1994 South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain,

Colorado Fire

Behavior Associated with the 1994 South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain,

Colorado

Fire Environment

Weather

Long Term—The South Canyon Fire Investigation

report states that “weather significantly contributed to the blowup

of the fire.” Below normal precipitation (as compared to the 30

year average) during the winter and spring of 1994 had pushed western

Colorado into a severe drought (South Canyon Report). Precipitation levels

at Glenwood Springs from October 1, 1993, through July 6, 1994, were 58

percent of normal. Accompanying the below-normal precipitation were much

warmer than normal temperatures through May and June. This pattern persisted

into July. Fires in western Colorado during the previous weeks had exhibited

rapid spread rates and long range spotting, both characteristic of drier

than average conditions.

July 5, 1994—On this day, weak high pressure aloft

and a hot, dry air mass covered western Colorado. Upper level winds were

light from the southwest through 14,000 feet and then increased to 30

miles per hour at 16,000 feet. At Grand Junction, CO, the lower atmosphere

was dry and unstable as indicated by a Haines Index of 6 (Haines 1988).

That morning a strong cold front developed in western Idaho. The front

was associated with an unseasonably cold upper level low pressure system,

centered over northern Oregon. By late afternoon the cold front extended

from eastern Idaho into central Nevada.

We are not aware of any weather observations taken by firefighters working

on the fire. The closest remote automatic weather station (RAWS) was southwest

of the airport at Rifle, CO, approximately 10 miles west of the fire site.

We assume that the measurements from Rifle are representative of the conditions

over the South Canyon Fire.

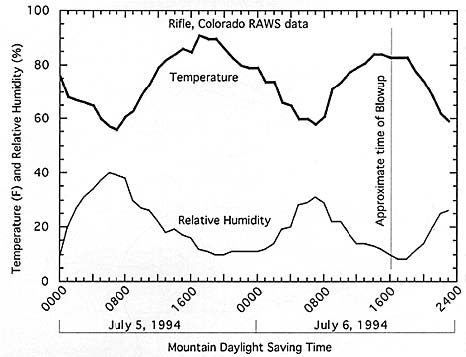

Between 0100 and 0600 on July 5 the relative humidity at the Rifle RAWS

ranged from 10 to 40 percent. Relative humidity remained near 11 percent

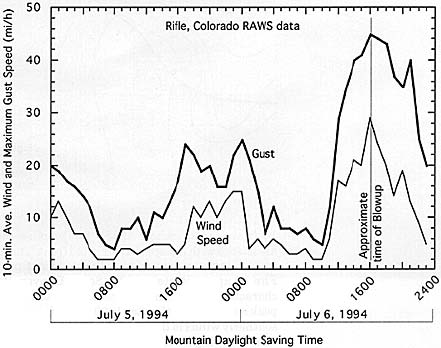

until after midnight (fig. 11). Winds at the Rifle RAWS were light and

variable through the morning and late afternoon of July 5, 1994 (fig.

12). By 1800 on July 5, 1994, winds over the South Canyon Fire area were

blowing generally from the south at 10 to 15 miles per hour with gusts

to 20 miles per hour (South Canyon Report; Bell 1994).

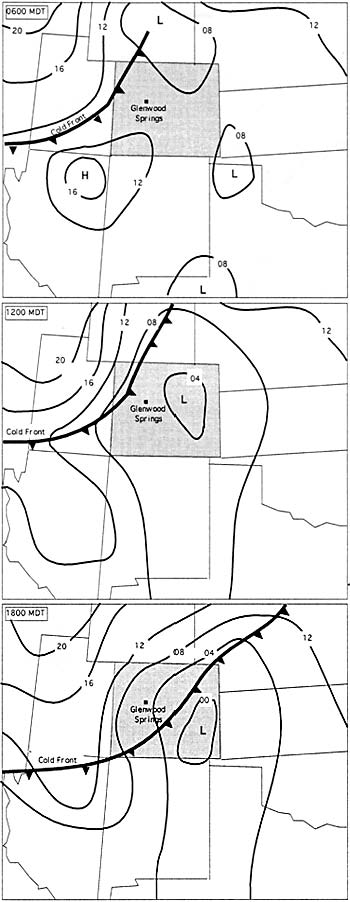

July 6, 1994—At 0600 this day, the cold front

extended from central Wyoming across northwest Colorado into southwestern

Utah (fig. 13). Relative humidity at Rifle reached a high of 29 percent

at about 0700 as compared to 40 percent the previous date (fig. 11). The

lower relative humidity during the early hours of July 6 enhanced burning

during the night. This is supported by witness statements that the fire

was more active through the night on July 5 than on previous nights.

The front passed over Grand Junction around 1300 and caused the 10 to

15 mile per hour winds to increase to approximately 30 miles per hour

(South Canyon Report). The front passed over the Rifle RAWS station between

1400 and 1500, as indicated by increased winds out of the west-southwest.

They reached their peak at about 1600 with gusts to 45 miles per hour.

The relative humidity at Rifle reached a minimum of 8 percent at 1700

on July 6. The winds at Rifle changed to the northwest at 1900. They gradually

decreased through the evening and were blowing less than 6 miles per hour

by 2300 (fig. 12).

Figure 11—Temperature and relative humidity measurements from the

Rifle, CO, Remote Automatic Weather Station for period midnight on July

5, 1994, through 2300 on July 6, 1994.

Figure 12—Wind speeds from the Rifle, CO, Remote Automatic Weather

Station for period midnight on July 5, 1994, through 2300 on July 6, 1994.

Figure 13—Surface air pressure charts showing progression of cold

front on July 6, 1994 (taken from original Accident Investigation Report).

Firefighters on the fire and at Canyon Creek Estates, a residential subdivision

about 2 miles west of the fire, noted an increase in winds between 1400

and 1430 (Scholz 1995). We surmise these were prefrontal winds associated

with the approaching cold front. The Accident Investigation Team meteorologist

estimated that the cold front passed over the South Canyon Fire at approximately

1520 (South Canyon Report). Witness statements characterized the winds

as continuing to increase in speed, reaching their peak strength shortly

after 1600. The original investigation report estimated southerly winds

in the West Drainage of 20 to 35 miles per hour and westerly winds blowing

across the ridges of 45 miles per hour at this time. Statements made by

firefighters and the helicopter pilot suggest that it is likely that gusts

over 50 miles per hour occurred in the chimneys and saddles along the

ridges. Smokejumpers near the Lunch Spot at 1606 estimated upslope winds

of 30 to 45 miles per hour (Petrilli 1995). Winds over the fire area remained

strong until 2000 (South Canyon Report).

Topography and Wind—There is inconsistent testimony

in witness statements regarding winds in the area of the fire. While the

general flow was from the west, the direction and intensity of the winds

varied significantly from one location to another (South Canyon Report;

Shepard 1995). For example, firefighters working on the Main Ridge stated

that as they cleared away brush from the fireline they could throw it

into the air and the wind would carry it over the side of the ridge. At

nearly the same time firefighters working on the northeast portion of

the West Flank Fire Line (a location topographically sheltered from the

wind) and at an exposed rocky outcropping near H-1 stated they experienced

almost no wind at all. Though inconsistent with each other, these observations

are consistent with the character of surface winds in complex mountainous

terrain, particularly when influenced by strong, synoptic-scale weather

patterns.

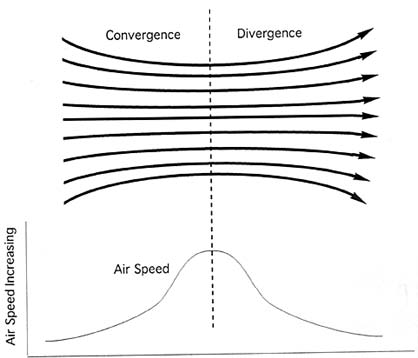

We feel topography was particularly influential on the surface winds

the afternoon of July 6. West of the fire site the Colorado River flows

through a relatively open and broad canyon. The low level westerly winds

accompanying the cold front passed through this canyon. The canyon narrows

dramatically about 2 miles west of the mouth of the West Drainage then

opens to the east near Glenwood Springs (fig. 7 and 14). As the wind flowed

from the broad canyon into the narrow Colorado River Gorge it increased

in speed (fig. 15).

Several factors combined to create unusually strong upcanyon flow in

the bottom of the West Drainage. First was the topography near the mouth

of the West Drainage. The orientation of the ridge running from the ignition

point, west to the Colorado River, acted as a “scoop” redirecting

a portion of the westerly flow in the Colorado River Gorge northward up

the bottom of the West Drainage (fig. 4 and 5). Second, normal daytime

heating of the upper slopes in the West Drainage induced general upcanyon

flow. This upcanyon flow resulted in a low pressure region at the entrance

to the West Drainage, causing even more air to flow from the gorge into

the drainage. Third, the increasingly strong westerly winds associated

with the cold front evacuated air from the top of the West Drainage (fig.

16). This resulted in pressure-induced flow from the Colorado Gorge into

the West Drainage. Some photographs and video footage taken during the

blowup show smoke movement (Bell 1994) and clearly illustrate the complexity

and turbulence of the surface winds shortly after 1610. High resolution

meteorological modeling (see appendix C) supports the mesoscale wind analysis

by the Accident Investigation Team meteorologist.

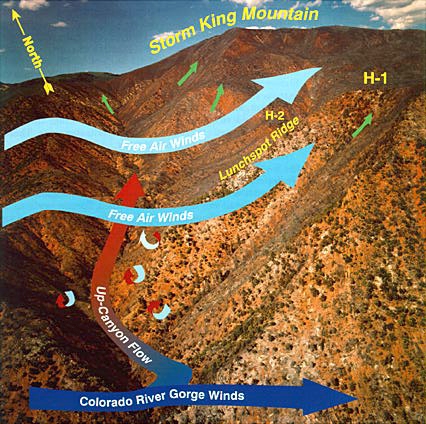

Figure 14—Aerial oblique photograph looking north over the Main

Ridge and Storm King Mountain from the south side of the Colorado River.

Note the widening of the river gorge as it opens into Glenwood Springs.

While not shown in this picture, the Colorado River Gorge again widens

to the west (off left side of photograph) of the fire site.

J. Kautz, U.S. Forest

Service, Missoula, MT.

Figure 15—Schematic diagram of venturi effect that caused increased

local winds where the West Drainage meets the Colorado River Gorge (not

to scale).

Figure 16—The general air flow over the fire area at the time of

the crown fire runs south of the Double Draws (about 1555). The free air

westerlies (light blue) evacuate the afternoon upslope flow (green) out

of the upper end of the West Drainage. This creates an area of divergence

in the north end of the West Drainage. The topography and orientation

of the mouth of the West Drainage redirected a portion of the strong winds

in the Colorado River Gorge (dark blue) up the West Drainage (red). A

shear zone is created where the westerly winds interact with the flow

up the West Drainage. Turbulent eddies created by the shear zone may have

enhanced burning near the Double Draw and along the Lunch Spot Ridge and

West Bench. The eddies transported burning embers north up the West Drainage.

J. Kautz, U.S. Forest Service, Missoula, MT.

<<< continue

reading—Fire Behavior at South Canyon Fire, Fire Chronology >>>

|