Camel Hump Falling Incident

Facilitated Learning Analysis

On July 25, 2008 a rappeller sustained a fractured vertebra when he was struck by a snag

that had been cut during a falling operation on the Camels Hump Incident. The incident

was analyzed through use of a Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA). The FLA team used

the After Action Review (AAR) format to review the events leading to the incident, the

falling incident and the medivac of the injured rappeller. The team was comprised of the

following personnel:

Anthony Engel, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie

NF

Keith Rowland, Okanogan-Wenatchee

NF

Kriste Solbrack, Okanogan-Wenatchee

NF

Steve Reynaud, North Cascades Smoke Jumpers (Retired)

The following contains a brief summary of the events leading to the incident, the results

of the AAR and recommendations from the team.

Summary

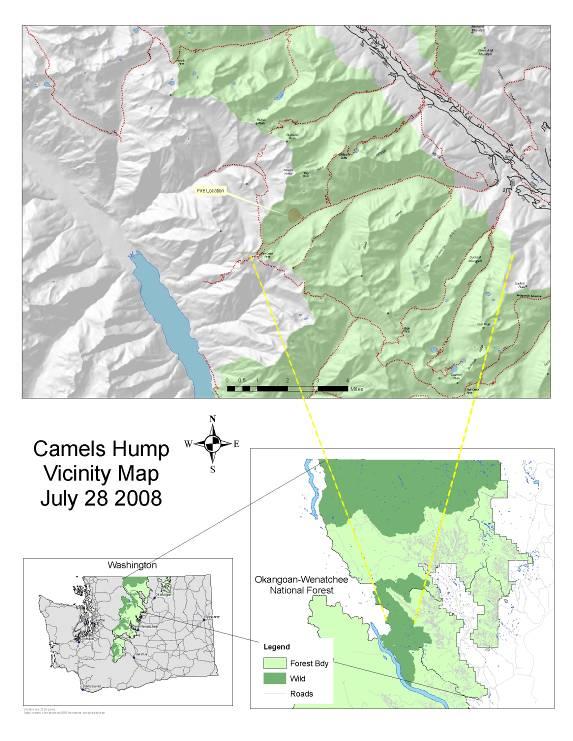

The Camel Hump Fire is located in the Lake Chelan-Sawtooth

Wilderness, on the

Methow Valley Ranger District of the Okanogan-Wenatchee

National Forest in

Washington State. The fire is remote and in steep terrain. In addition, the fire area is

within the 1994 War Creek burn and the area is predominantly comprised of snags and

downed logs.

A Type 3 team was assigned to the fire and implemented a contain and control strategy

using hand crews with helicopter support. On July 25, a rappel team was assigned to open

up a dip site that had been used to support bucket operations on the fire. The initial

assessment indicated the need to remove snags to improve ingress and egress for bucket

operations. The dip site is a small pond approximately three miles from the Camels

Hump Fire and within the 1994 War Creek burn.

Upon reaching the dip site the rappellers identified additional snags to be removed. Four

rappellers were dropped to the site and were organized into two saw teams. Saw team 1

consisted of a cutter and the rapeller in charge. This team began to clear snags on the

north side of the dip site pond to provide a more efficient ingress for buckets entering the

pond. The team had worked for about two hours and had about two trees left to complete

snagging the ingress.

At the time of the incident, the cutter on saw team 1 signaled his swamper and verified

his intent to fall an approximately 35 ft. tall, 18 dbh inch snag. His swamper, the rappeller

in charge, was up hill and in the direction of the snag’s lean. The snag had a heavy lean

and was severely catfaced

(burned out portion of the tree bole) on the back cut (down

hill) side. The cutter back cut the tree and saw that his swamper was in the direction of

the fall. The top of the tree struck the hard hat of the swamper.

Notifications and initial assessments of the injured rappeller were made by the cutter

immediately. Saw team 2 improved the opening north of the pond into an evacuation

landing zone and cleared a travel route from the helispot to the injured rappeller. A

helicopter with 2 EMTs arrived at the site. The injured rappeller was checked, stabilized

and loaded on the helicopter. The injured rappeller was flown directly to Central

Washington Hospital in Wenatchee for treatment.

It is notable that the medivac operation preformed on this incident was nearly flawless.

Evacuating an injured person from a remote site is a complex process with a number of

time sensitive and interdependent tasks. Throughout the process decision making

authority moved fluidly to individuals with the most relevant knowledge of the situation.

Decisions were made; actions were taken and then communicated decisively at all levels.

The rapellers on site, the lookout,

the helibase personnel and the incident commanders

on the fire exemplified the High Reliability Organization (HRO) principle “deference to

expertise” (Weick and Sutcliffe) in all phases of this medivac.

Facilitated After Action Review (AAR)

On July 27 the FLA team facilitated an AAR with members of the rappel and incident

command organization. The AAR was confined to the dip site snagging operation, the

injury incident and the subsequent medivac.

The intent of the AAR was to:

- Provide the participants with a common understanding of what had happened

- Identify what worked well

- Identify what could be done better next time

Note: Saw team 1 was comprised of 1 cutter and the rappeller in charge who also served

as swamper for the saw team.

The AAR format was used and the following bullets summarize the findings of the group:

What was planned?

- Snags needed to be taken out to give better ingress and egress to the dip site.

- The dip site had been used for 1.5 days, when operations asked for the snags to be

taken out.

- A bucket strike of a tree had been observed in the fire area; though not at the dip

site location.

What actually happened?

- A spotter, trainee spotter and 4 rappellers flew to the site.

- The decision was made to insert 4 rappellers to remove snags at the dip site.

- Mission started at approximately 1600.

- A human repeater who also served as a lookout was in place.

- One 2 person team (team 1) worked on the ingress, and one 2 person team (team

2) worked on the egress.

- Mission estimated to be completed by 2030.

- Operational tempo was normal and not hurried.

- Team 1 had worked for two hours prior to incident, had 2 trees left to remove.

- Rappeller in charge was attempting to contact air attack to arrange back haul of

rappel gear and walked up hill from the snag to obtain better reception.

- Cutter and rappeller in charge had eye contact.

- Team 1 cutter signaled (hand motion) where the tree was going to go.

- The swamper acknowledged.

- There was a heavy cat face on the tree (down hill side) to be cut which shortened

the time for the tree to be felled.

- Swamper had not moved out of the way after cutter looked up from the completed

back cut.

- Swamper began to move out of the way and continued to attempt calls to air

attack.

- Swamper was struck on the top of the hard hat and fell to the ground

- Team 1 cutter made a couple attempts to contact air attack to notify need for a

medivac.

- Lookout heard the attempts, and called team 1 faller.

- Team 1 faller requested EMT 1 and EMT 2.

- Lookout confirmed nature of emergency with Helibase at 1810 and requested

EMT’s.

- Team 1 faller identified helispot location and asked Team 2 to open it up.

- Team 2 began to cut helispot on adjacent high spot; were redirected to a clear area

adjacent to the dip site pond by the recon helicopter.

- When the helispot was complete Team 2 cut a trail from injury site to helicopter.

- EMTs planned who would assess the injured and who would get the back board

ready, etc.

- Type II helicopter with EMTs arrived at site at 1835.

- At 1837 helicopter landed on scene.

- EMT assessed, packaged and loaded the injured person.

- Lat and longs for the Wenatchee hospital were given to the pilot before it was

determined they were needed just in case, at 1845.

- At 1857 the helicopter departed helispot for the hospital.

- Injured rappeller arrived hospital 1934.

Why did it happen? (What was the intent?)

- Operation to make a safer dip site and to reduce the risk to pilots if we can.

- Make the turns more efficient from dip site to fire; using less power for

ingress/egress.

- Both cutter and swamper lost situational awareness of each other.

- After eye contact was made, faller went on to focus on cutting the tree.

- Swamper was within 2 tree lengths of the snag.

- Swamper thought he had more time to exit the area and was surprised by how fast

the tree fell.

- Swamper was distracted by radio communications and back haul mission.

- Saw team 1 had worked closely as a team prior to this mission and had worked

well together throughout the day.

- While team #1 faller was cutting the last two trees, the swamper was trying to

contact air attack and was having problems.

- The falling teams didn’t feel rushed. They had decided the operation was going to

take long enough to have to stay out over night.

What worked well?

- Felling crew had cut about 40 trees and the operation was working well and

moving fluidly.

- Crews have worked together, trained together, have good team familiarity, and

cohesiveness; this made the medivac efficient.

- The lookout/human repeater had two radios worked well to manage different

frequencies, scanned, particularly during an emergency.

- Preidentifying

potential medivac spot.

- Considering the severity of the situation, the crew focused on the tasks during

medivac, not letting emotions override their training and experience.

- Human repeaters were experienced, they are a critical resource.

- Assessed risk of mission by weighing risk to pilots vs risk to firefighters.

What can we do differently?

- Take time to reassess the situation.

- Be aware of site, swamper, and operation.

- Get back to basic Hazard Tree Risk Management SOPs; including separation

distance and securing the falling area.

- Beware of complacency. Two cutters had worked together many times and were

familiar with each others habits; anticipating actions and outcomes vs. focus on

SOPs.

- Share expectation of maintaining SOPs with other crews and other resources; face

to face – human element.

Recommendations

The following recommendations were derived from the AAR and from discussions with

members of the rappel crew and FLA team members:

1. Focus on Hazard Tree Risk Management Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Hazard Tree Risk Management SOPs need to be followed consistently in every cutting

operation. Each of these procedures has been developed to mitigate risk in an inherently

hazardous job. Separation distances and securing the cutting area are the responsibility of

everyone taking part in the operation.

In this case the members of the saw team had worked together many times and were

familiar with each others habits, where able to anticipate the actions of the other and the

outcomes of those actions. This is the strength of a cohesive, high performance team.

This strength can become vulnerability when used in place of SOPs; anticipating actions

and outcomes may cause a lack of focus on SOPs and leave people vulnerable to errors

and unpredicted outcomes. SOPs provide a margin of error between fire fighters and

unanticipated events.

Recommendation: Crew leaders and crew members should use this FLA to reinforce the

importance of adherence to Hazard Tree Risk Management SOPs.

2. Identify barriers to good Situation Awareness (SA)

1. Distractions: Distractions are the norm in incident management and can limit SA. In

this incident the swamper was talking on the radio. He was focused on obtaining good

radio communication and arranging a back haul task that needed to be coordinated with

other missions on the fire. This would have distracted him from paying full attention to

the cutter and the snagging operation. Similarly, the cutter’s primary focus narrowed to

making the cut resulting in the loss of cutting area SA.

2. Misperceptions: The cut snag was down hill from the swamper’s location. This could

have caused him to misjudge

the height of the tree and thus the time it would take to

gain appropriate separation distance. Further, the snag was severely catfaced

on the

down hill side. To the swamper, the snag appeared to be a full tree bole. This may have

caused him to misperceive

the time it would take to cut the tree and further distorted his

perception of the time it would take to clear the site.

3. Complacency: Complacency can be an over used word. Preoccupation with failure and

the reluctance to simplify enable high performance teams to guard against complacency.

These two core HRO principles were evident in the planning and implementation of the

dip site mission. The rappellers functioned as a cohesive, high performance team. However, high performance teams can become vulnerable to simplification and the loss

of a preoccupation with failure because of their inherent ability to anticipate team

member’s actions and their outcomes.

Both members of saw team were well trained and experienced. They were very familiar

with each other and had worked very well together throughout the day. They had been

performing well, communicating well and had been able to anticipate actions and

outcomes throughout the operation (reluctance to simplify). HROs tend to be wary of

quiet times and operations that are working well. The saw team’s ability to anticipate

each other’s actions and the outcomes of those actions may have been used in place of

some Hazard Tree Risk Management SOPs (preoccupation with failure). The saw team

would have been more likely to maintain SOPs if one of the team members were a new

fire fighter or if they had not known each other.

Recommendation: SOPs provide a margin of error that can make a team more resilient

to unanticipated events. Mindfulness of potential barriers to SA and adherence to SOPs

should be discussed in briefings and during operations.

3. Communicate what was learned

The best way to help others learn from this mishap is to share our individual roles that we

played in this specific incident at every opportunity with all firefighters. Present the

incident from a first hand and personal point of view. In doing so, we are more likely to

connect with other fire fighters on an emotional level with intent that those not involved

will see and feel the importance of what we have learned.

Recommendation: Adherence to SOPs should be communicated as a standard from a

personal point of view. Further, these standards should be communicated as part of the

pride of workmanship and professionalism that is inherent in all other aspects of the

mission.

|