Lessons Learned

“Safety

Zone” newsletter, July, 2004

Lessons Learned —

author, date unknown

One-Year Anniversary Letter

by Kelly Close, FBAN

Declaration on Cramer

Redactions, by James Furnish, April, 2005

FSEEE v. USFS, FOIA

Civil Lawsuit Order,

December, 2005

FOIA

Request to USFS, December, 2005

FOIA Appeal to USFS,

February, 2006

Management Evaluation Report

Investigation Team Information

Synopsis of the

Cramer Fire Accident Investigation

Causal Factors

Contributing Factors

Addendum

Factual Report

Executive Summary

Narrative

Background

(facts 1 - 57)

Preaccident

(facts 58 - 201)

Accident

(fact 202)

Postaccident

(facts 203 - 237)

Findings

Appendix A

Resources on the Fire

Appendix B

Cramer Fire Timeline

Appendix C

Fire Behavior and Weather

Prior Conditions

Initial Phase

Transition

Phase

Acceleration

Phase

Entrapment

Phase

Appendix D

Equipment Found at H-2 and the Fatalities Site

Appendix E

Fire Policy, Directives, and Guides

OIG Investigation

OIG FOIA Response,

February, 2005

2nd FOIA Request to OIG,

April, 2006

2nd OIG FOIA Response,

August, 2006, (1.4 mb, Adobe .pdf file)

OSHA Investigation

OSHA Cramer Fire Briefing Paper

• Summary and ToC

• Sections I-IV

• Sections V-VII

• Section VIII

• Acronyms/Glossary

OSHA South Canyon Fire

Briefing Paper

Letter to District

Ranger, June 19, 2003

OSHA Investigation Guidelines

OSHA News Release

• OSHA Citation 1

• OSHA Citation

2

• OSHA

Citation 3

USFS Response

OSHA FOIA Letter

Adobe PDF and Microsoft Word versions of documents related to

the Cramer Fire can be downloaded from the U.S.

Forest Service website.

|

Accident Investigation

Factual Report

Cramer Fire Fatalities

North Fork Ranger District

Salmon-Challis National Forest

Region 4

Salmon, Idaho - July 22, 2003

Appendix C—Fire Behavior and Weather

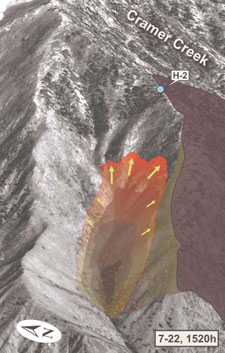

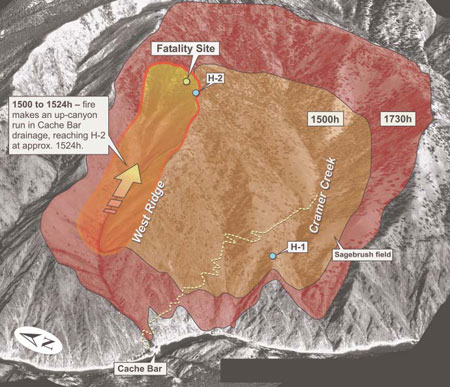

Entrapment Phase, July 22 (1500 to 1524)

By 1500, the short wave disturbance had moved over the fire area. It

brought strong winds from the northwest, shifting to westerly, that overpowered

local diurnal winds. Driven by these strong winds, the fire began to make

rapid, intense runs simultaneously in Cramer Creek and the Cache Bar drainages.

At H-1, gusts up to 30 mph were reported, and crews in that area moved

into the black as a safety zone. In Cramer Creek, the fire intensity was

rapidly building on the northwest perimeter, and transitioned from a surface

fire to a crown fire as windspeeds increased and the fire encountered

more continuous crown fuels. A large, brown column formed in the Cramer

Creek drainage, pushing vertically to 12,000 feet and moving eastward

toward the town of Salmon, ID.

An active, moving fire front had become established in the bottom of

the Cache Bar drainage (figure 25). Pushed by strong winds, the fire front

began to move upcanyon toward H-2. As the wind shifted to a more westerly

flow, winds aloft began to align with the Cache Bar drainage. The fire

moved rapidly upcanyon (figure 26), with spread rates and intensities

much greater than witnesses had expected. Preliminary modeling indicated

that during the early part of the run in the drainage bottom, the fire

was moving through the ceanothus brush at a rate of 80 to 90 feet per

minute with flame lengths up to 9 to 12 feet.

Figure 25—Between

1430 and 1440, smokes in the bottom of the Cache Bar drainage turn into

a flaming front.

Figure 26—At 1500,

a fire front begins to move upcanyon and up to the base of the slope below

the West Ridge.

As the fire advanced up the Cache Bar drainage, it began to burn up the

slope below the West Ridge through green and underburned brush and downed

woody fuels (figure 27). The entire upper portion of the Cache Bar drainage

erupted into flames which ran uphill. Flame lengths averaged 20 feet in

brush and 50 feet at the leading edge. The fire was not one solid front,

but simultaneous movement of smaller fronts that followed stringers of

more continuous fuels. When the fire encountered rocky areas on the slope,

the fire front did not stop—flames swept over them as if the rocks

were burning as well. Postfire modeling indicates the spread rate was

130 to 150 feet per minute (fuel model 6), consistent with witness descriptions

of the event (figure 28). Actual flame lengths witnessed and evidenced

by tree/snag bole scorch height exceeded that predicted for fuel model

6. This may have been partly due to the brush being dried and preheated

by the backing fire earlier in the day.

Figure 27—Between

1513 and 1520, the fire front intensifies and continues to move upslope

below the West Ridge.

Figure 28—At 1520,

the fire front, based on a model projection, reached the base of the ravine

below H-2.

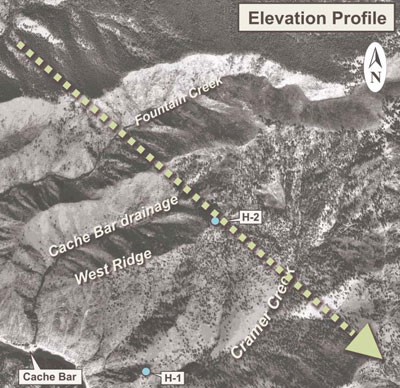

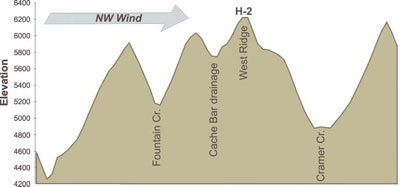

At 1520, the fire reached the upper portion of the Cache Bar drainage

that was more exposed to the prevailing winds. An elevation profile of

this area shows the exposure of the slope below H-2 to prevailing northwest

winds (figures 29 and 30). Winds at H-2 were estimated at 20 to 25 knots.

The entire upper portion of the drainage appeared to erupt simultaneously

into flames, moving rapidly upslope and updrainage as a “big flash

front.”

Figure 29—Location

of elevation profile line in figure 30.

Figure 30—Elevation

profile along a line from northwest to southeast, running through H-2.

The air attack pilot noted that as the fire in the Cache Bar drainage

increased in intensity after 1500, strong indrafts were produced, indicating

extreme burning conditions. At the leading edge of the fire, updrafts

caused the plane to gain 1,000 feet, and at the trailing edge of the fire,

downdrafts would cause the plane to drop 1,000 feet when the plane passed

through those areas.

As the fire increased in intensity and speed and burned up the brush-covered

slope in the Cache Bar drainage, it laid closely against the slope. The

smoke movement also remained close to the slope rather than forming a

more vertical column, rolling over the West Ridge and eventually joining

the main column in Cramer Creek. When the fire front moved into stands

of trees in the upper part of the drainage, it did not immediately consume

the canopies. Crowns at the lower end of these stands were dried, but

not scorched. Bole and crown consumption indicate the flaming front remained

close to the ground, gradually moving higher into the crowns as it progressed

up the slope. The fire did not begin to fully involve the canopy until

about halfway into the stands (figures 31, 32, and 33).

Figure 31—View

of the ravine at the base of the slope below H-2 in the Cache Bar drainage,

from below the stand of trees under H-2.

Figure 32—At 1523,

the fire front, based on a model projection, reached the base of the stand

of trees below H-2.

Figure 33—At 1525,

the fire front, based on a model projection, reached H-2.

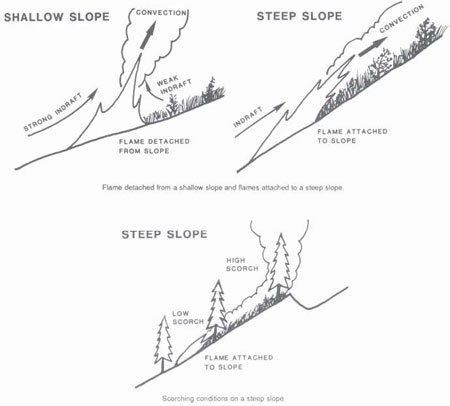

The descriptions and postfire signs of fire spread in the Cache Bar drainage

indicate the possibility of a phenomenon Richard Rothermel described as

“flame attachment” to a slope. This occurs when fire is burning

on a steep slope and the convection from the fire cannot move away from

the slope. The result is that convective heat and the main part of the

flaming front stay closer to the surface, preheating the fuels and increasing

the intensity of the flaming front as it passes through an area (figure

34). Figures 35 through 38 show crown drying, directional needle and branch

freeze in conifers, and crown consumptions patterns that indicate flame

attachment on the slope below H-2.

Figure 34—Descripton

of the “flame attachment” phenomenon.—From Richard Rothermal,

1989 BEHAVE fire prediction and fuel-modeling system, BURN subsystem part

2.

Figure 35—Crown

scorch and consumption in the stand of trees below H-2 (foreground), indicating

flame attachment as described in figure 34.

Figure 36—Crown

consumption and directional needle freeze in the stand of trees below

H-2.

Figure 37—Upslope

needle freeze at the base of the stand of trees below H-2. Crowns were

dried but not consumed by the fire in the lower portion of the stand.

Figure 38—Upslope

needle freeze on the ridgeline immediately west of H-2.

When the fire front reached H-2, postfire site conditions indicate that

surface temperatures were from 1,300 °F to potentially over 2,000 °F in

the crowns. Flame lengths were reported to be 50 to 100 feet as the fire

moved to the top of the stand of trees below H-2 (figure 39). Reports

of spread rates in the upper part of the Cache Bar drainage vary, but

are consistent with the preliminary modeled spread rate of 400 to 600

feet per minute (4.5 to 6.0 miles per hour) during the final run from

the base of the slope below H-2 to H-2.

Figure 39—The

upper Cache Bar drainage after the fire front passed.

After reaching H-2, the fire continued to spread beyond the upper end

of the Cache Bar drainage to the east, burning into part of Fountain Creek.

By 1730, all of Cramer Creek had been burned and the fire had moved eastward

into Long Tom Creek. Figure 40 shows the estimated fire perimeter at 1730

on July 22, 2003.

Figure 40—Cramer

Fire perimeter and spread on July 22, 2003, from 1500 to 1730 (estimate).

<<< continue

reading—Appendix D>>>

|